Classicist Peter Green is an inspiring scholar, translator, and novelist. I've quoted from his excellent

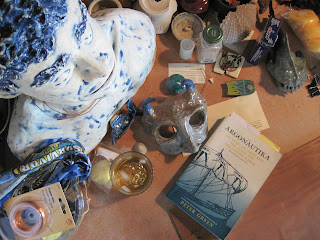

The Laughter of Aphrodite: A Novel About Sappho of Lesbos here, and now I'm returning to his translation of Apollonius of Rhodes' epic poem of Jason and the Argonauts. I picked up this book eleven years ago for my 40th birthday, and as my 51st approaches, it feels right to revisit a favorite tale of adventure and desire.

I'd like to quote Green on translating this epic poem as a "labor of love" and on formative experiences regarding scholarship and, more importantly, reading for enjoyment. I'm in Green's camp, quite obviously, and I have a deep attachment to tales of the heroic Greeks as well.

In his "Preface and Acknowledgements," Peter Green writes:

Working on the Argonautika has been for me very much a labor of love. At the age of seven I first encountered, and was fascinated by, the quest for the Golden Fleece in that brilliant volume by Andrew Lang, Tales of Troy and Greece, never yet surpassed as a retelling of ancient myth for young people.* Years later, reading Boswell's Life of Johnson, I came across this passage:

"And yet, (said I) people go through the world very well, and carry on the business of life to good advantage, without learning." Johnson: "Why, Sir, that may be true in cases where learning cannot possibly be of any use; for instance, this boy rows us as well without learning, as if he could sing the song of Orpheus to the Argonauts, who were the first sailors." He then called to the boy, "What would you give, my lad, to know about the Argonauts?" "Sir, (said the boy) I would give what I have."

The boy's words, then and even today, struck an emotional chord that hit me directly and physically, just as a certain high-frequency note drawn from a violin will shatter a wineglass. In one sense I have been giving what I have in pursuit of those bright, elusive, infinitely rewarding Sirens ever since. The anecdote seems to me the best justification ever put forward for a truly humane education.

This is, I know, quite hopelessly old-fashioned and romantic. Robert Graves somewhere recalls his dismay at the reply he got from an earnest student of English literature when he asked her what she enjoyed about Shakespeare's (I think) work. "I don't read to enjoy," she said, in withering reproof, "I read to evaluate." The absence of genuine pleasure is what makes too much literary criticism today an aridly sterile desert. Despite this I still retain my deep instinctive responses to great art and literature, though a quarter of a century's exposure to American academic critical trends has come as near to killing such reactions in me as anything could do. In that sense the present work may count as an act of calculated defiance, as well as an invitation to relish one of the Hellenic world's oldest and most deeply resonant myths, told by a master of his craft, who loved the sea, and ships, and the complexities of human nature, and let that passion irradiate everything he wrote.

--from The Argonautika: The Story of Jason and the Quest for the Golden Fleece by Apollonios Rhodios, Translated, with Introduction and Glossary By Peter Green,

University of California Press: Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1997: pages xii-xiii.

I'd almost forgotten Green's footnote to the passage above. Here it is:

*

Lang, together with The Heroes of Asgard

and several other highly formative texts, was put into my hands during the three years, form six to eight, that I spent at an English P.N.E.U. (Parents' National Educational Union) school, before being transferred to the less congenial rigors of prep and boarding schools. Most of the serious permanent passions of my later life (including the study of classics as a profession, and the absorption of world literature and music for the sheer fun of it) had their roots in my P.N.E.U. days. I did not get any remotely comparable stimulation and excitement until I returned to Cambridge after World War II as an elderly (I

thought) I was twenty-three) ex-service undergraduate.